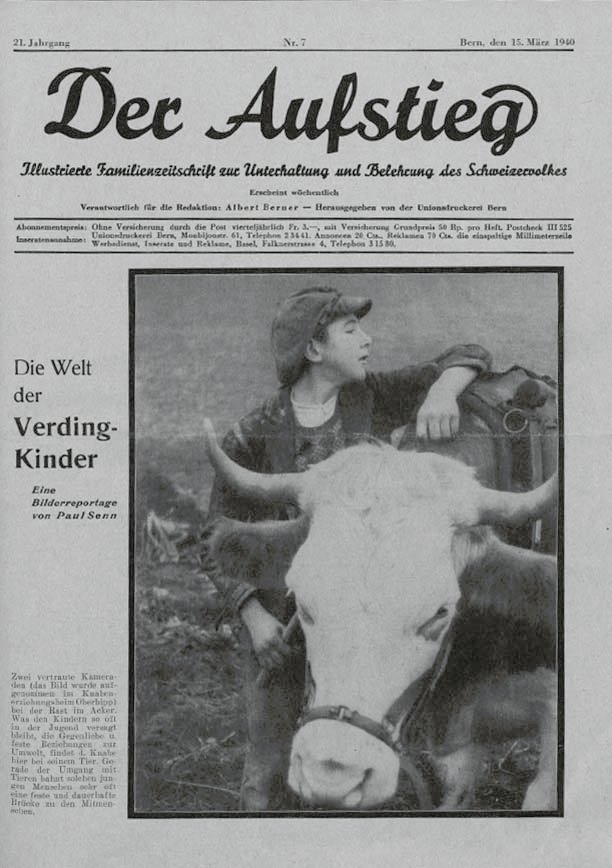

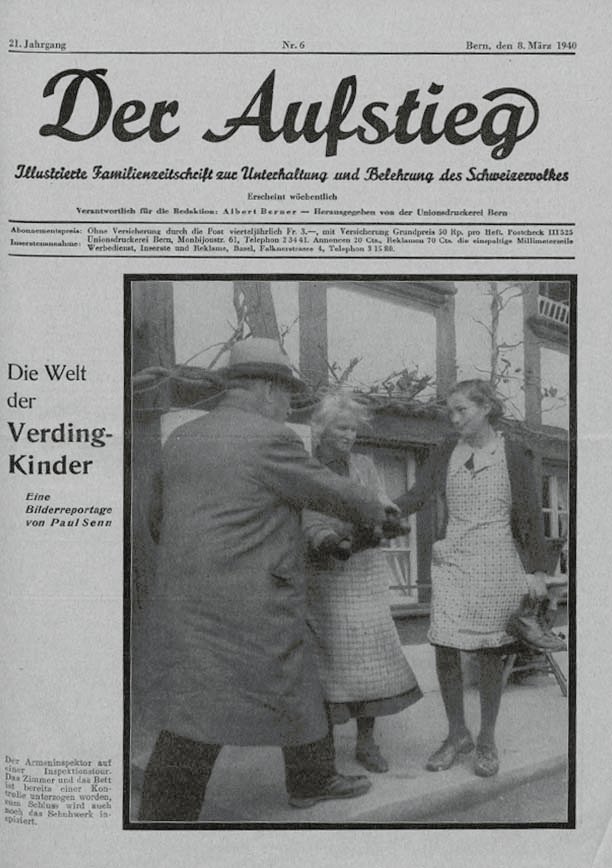

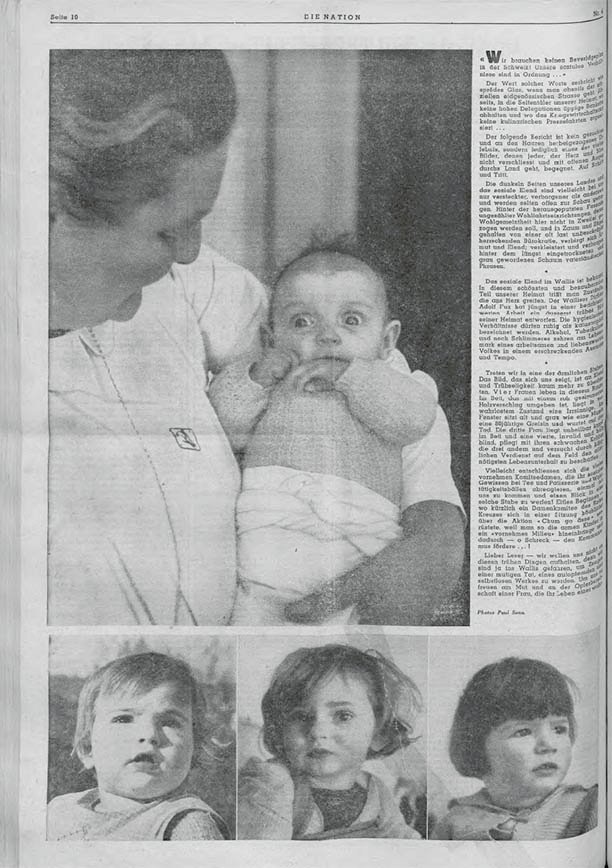

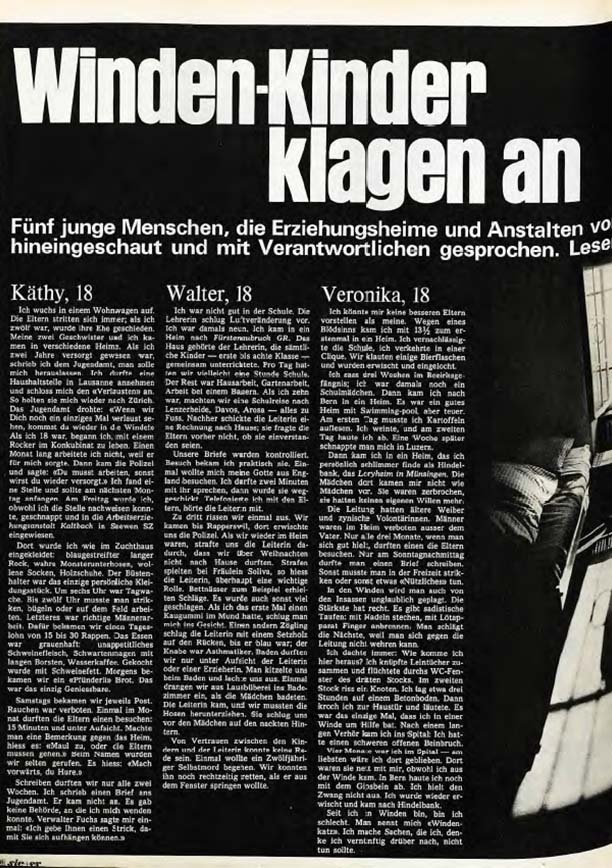

Indentured children

The history of the Indentured children in Switzerland

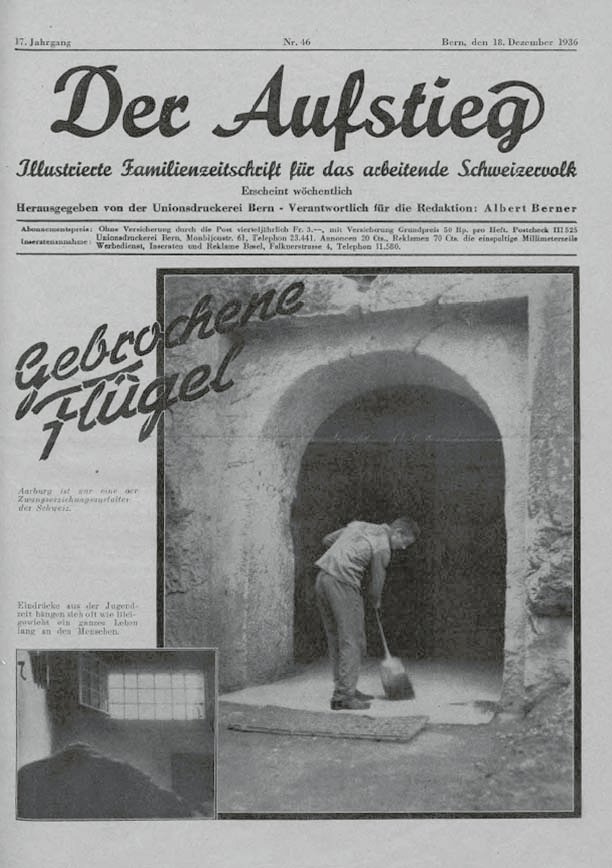

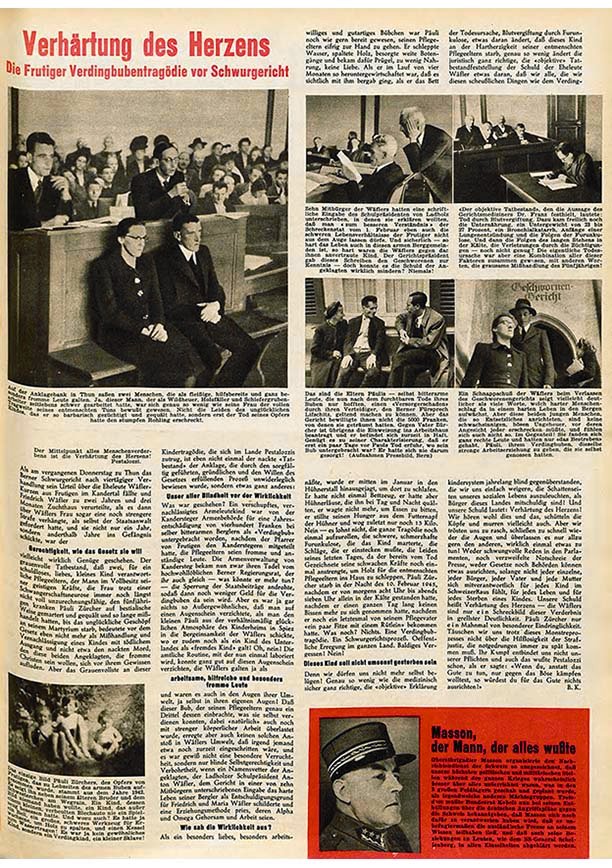

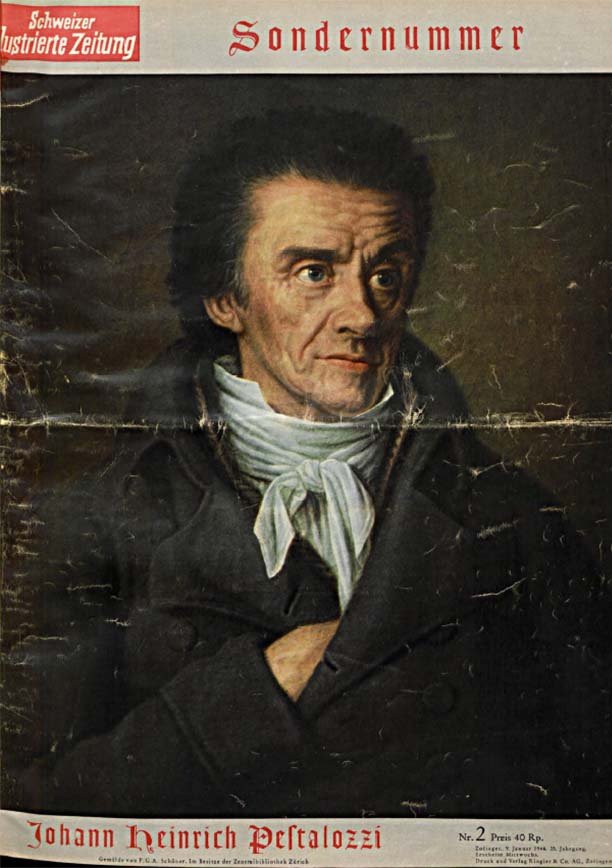

The so-called “Forced placement” is one of the darkest chapters of Swiss social policy. For centuries, children whose families were destitute or who were considered half or full orphans were taken away from their parents by state authorities, initially placed in orphanages and later given to farming families. There they had to work until they finished school – usually without pay and under degrading conditions.

This practice was characterized by exploitation, neglect and exclusion. Many children suffered from hard work, malnutrition, lack of hygiene and physical, psychological and sexual violence. Separation from siblings and exclusion from the education system made it difficult for them to lead an independent life.

This system was only gradually ended in the 1970s. For many of those affected, however, what they experienced remains a serious legacy with social and psychological consequences to this day.

This past shows how far-reaching state intervention in family life can be, especially when there is a lack of control. This is why our association is now campaigning for reforms in child and adult protection. The aim is to strengthen the rights of children, parents and those affected and to align state action with proportionality and constitutional principles.

Activities and commitment of the association

The main task of the association is to represent the legitimate interests of those affected. In its public relations work through its own homepage, interviews, conferences and readings, the association communicates the topic to current society. As an important showcase, the monthly newsletter documents various aspects of forced outplacement. Eight years ago, the association also started a broad-based specialist library, which now comprises over 900 works in 4 languages. Of these, just over 400 titles are already on loan from the Swiss. Social Archives in Zurich for students to borrow. In 2019, over 300 more works will be added in German, Italian and English, as well as around 220 titles in French. The association was also able to create a media library comprising more than 150 titles on DVD thanks to a donation to mark its 10th anniversary.

The association was also actively involved in preparing the official apology event on April 11, 2013 at the Kulturcasino in Bern. There is close cooperation with historians and other victims’ organizations across linguistic and national borders.

The association actively campaigned for financial compensation for the victims from the federal government. It was also represented at the round table set up by Ms. Simonetta Sommaruga in 2013. There, he put forward the demands for a competence center, a documentation office and easier access to the personal files of those affected. Together with allies, the association finally demanded a comprehensive scientific research study on the social history of Switzerland in this context.

Almost three years ago, together with the agency keystone/SDA and the photographer Peter Klaunzer, a portrait exhibition with short biographies of alumni was created, which has already been shown at two locations in Switzerland.

A research project on the photo-historical reappraisal of the Verdingkinder story was also developed. Over the last 10 years, the association has produced various publications and carried out two pilot studies on important topics. The association is currently preparing further research and pilot studies on various as yet unresolved topics.

The association is open to new members.

Walter Zwahlen on the aims of the association:

Article Berner Zeitung, 8. 12. 2011 (pdf)

www.netzwerk-verdingt.ch

E-mail: info@netzwerk-verdingt.ch

Office:

Verein netzwerk verdingt

Oberdorfstrasse 19

3066 Stettlen

Contemporary witnesses

David Gogniat

Read more

Because my father suddenly left the family, we were all given a guardian. But my mother fiercely fought for us. In 1948, my three younger siblings were sent together to a foster family in Feutersoey. I myself went to the 3rd primary school in Bern. One day in April 1949, two policemen turned up at our house and wanted to pick me up for an official placement. As my mother was a very sturdy woman, she threw the two policemen down the stairs from the mezzanine. A day later, three policemen turned up and enforced the authorities’ verdict. But my mother accompanied me to the care home, also in Feutersoey. I was placed with a childless farming family and had to replace a farmhand right from the start, as the foster father was partially disabled. I was forced to stay there until I finished school.

We only had school in winter. From spring to the end of fall, we were on the alp, where I was used as a farmhand. On the farm in the valley, the daily watch began at five o’clock in the morning with stable work. As the farmer was a lazy dog, he usually didn’t go into the barn until five o’clock in the afternoon, so mucking out, feeding and working with the pigs often took me until after 9 pm. Then we had dinner. I didn’t have time to do my schoolwork until 10pm. Pure drudgery and exploitation. As the farmer was a sneaky guy, I wasn’t allowed to milk and only learned to do so later. I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone about it.

Ms. Madörin from the City of Bern’s Youth Welfare Office only came to visit once a year by appointment. I was specially dressed for the occasion and was promised not to complain. I didn’t have to work that day and was given a decent snack. I never saw my guardian during this time. I was never in the room that was shown to the “inspector”. I slept in the unheated hallway. Despite my disability, my foster father was always ready to punish and beat me.

At the end of school, I actually wanted to become a mechanic. Because an apprenticeship was expensive at the time, it was out of the question, and the only options were chimney sweep, farmer or gardener. So I opted for the farmer apprenticeship. Mr. Wyss from the Youth Welfare Office of the City of Bern accompanied me to the chosen place. On the long train ride to Welschland, he told me that I should have told Ms. Madörin about the problems at the care home in Feutersoey, then the authorities would have intervened. He ignored the fact that I had had no opportunity to do so.

A childless farmer was prepared to take me on for the year of my farming apprenticeship, but made it a condition that I complete my training in Rüti near Bern, as I was then intended to succeed him on his farm. I completed the second year of my apprenticeship on a farm in Bätterkinden. When I wanted to return to Geneva, the tractor driver of the large farm in Bätterkinden had an accident. The two farmers agreed that I could only leave this temporary job in the fall at the request of the Geneva farmer because of the predicament. This Geneva farmer tried to reach me twice by phone and I should have called him back. These calls were not returned out of self-interest on the part of the Bätterkinder farmer, as he did not want to do without my urgently needed labor. Because the house telephone was installed in the bedroom, these contact attempts remained hidden from me. On the third call, I happened to be there and the farmer’s wife put me through to the first teacher.

After learning of the infamous situation and the nasty deception, I became so angry that I decided to give up farming. I then took the lorry test and worked as a chauffeur for a few years before setting up my own business in 1964. My mother stayed in Bern and worked as a cleaner after the family had been torn apart by the authorities’ decision, we four children had been hired out and my biological father and I had divorced. She still had to pay for our board from her meagre salary. In the correspondence I found after her death, I realized that she had fought for us children like a lioness. I am eternally grateful to her for that.

Charles Probst

As a small child, barely a year old, Jean was placed with foster parents and a few years later was hired out to a farmer. He did not see his biological mother again until he was 11, but he was unable to return to her and her family. Despite being in a foster home, he managed to prove himself in an apprenticeship and in life.

Read more

Charles Probst: Why did I become a Verdingkind?

What was kept from me as a child

It was only as an adult, around 1950, that I began to ask myself questions about my origins and the past lives of my parents. I couldn’t find out anything about my supposed father’s childhood. My relationship with him was frosty. I didn’t dare to do many things that my brothers were allowed to do. He repeatedly said to my brothers that I wasn’t his. This made me prick up my ears and I started to ask my mother about it. She then confessed to me that she had worked as a maid on a farm in Heimiswil from 1926. There, the farmer at the time got her pregnant with me. When the affair became public, she was dismissed, as she was only a maid. My biological father shirked his responsibility and never paid any alimony. Fortunately, my mother soon found work as an office girl at the Hotel Bristol in Bern. There she met my stepfather, who then pretended to be the child’s father. He worked as a miner in tunnel and power station construction. Then he had to go to the spa for health reasons. The Salvation Army probably supported him financially at the time. However, he broke off the cure prematurely and returned to his loved ones. He was now unemployed, and there was no unemployment benefit at the time. This left the whole family destitute. My mother had to take care of the household alone. Only the family doctor knew about the precarious situation. He therefore ordered that the boys were also sent for treatment and placed under tuberculosis control. As the eldest, I was under guardianship and was put out to work. When my stepfather became unemployed, the guardianship authorities even applied for him to be placed under guardianship, for the household to be dissolved and for the children to be placed with him. Fortunately, my stepfather was able to prevent this, he knew he was in the right and fought back. Even during my mother’s last pregnancy, the guardianship authorities insisted that she be stopped. She resisted this request, but had the procedure carried out in 1935. During the Second World War, my father was in military service. The mother had to see for herself how she could cope with the situation and the two children. Not an easy task with the food rationing and the meagre wages for women. There was also no income replacement for those doing military service. The Winkelried Foundation for such hardship cases already existed at the time. However, those in real need knew nothing about it and were not informed, although the company commanders were aware of it. Out of necessity, the mother had to place another boy in a foster home. Even though there was now one less eater at the table, Schmalbart remained a guest. The youngest boy was confirmed in 1949. Because there was no money for new shoes for this occasion, I had to swap my shoes with my brother as the oldest. I bought these shoes in Freiburg with the apprentice’s tip. Despite working hard, I always lacked the bare necessities. By today’s standards, my parents were among the working poor. Pasta, bread and black coffee without milk were the be-all and end-all of their diet. There was rarely enough for more. When the cousin came to visit, my mother had to borrow money from the neighborhood to be able to buy milk at all. The apartment at the time was a dump. The authorities knew about it, but did nothing to improve the situation for the family. There was no running water in the kitchen and the outhouse was far away from the house. The parlor floor made of rough fir strips was treacherous, as I kept getting my cleaning rag stuck to it when I swept. My parents had a bad life. My mother had to suffer even more, her stepfather also beat her. Even with her family, she still had a miserable life. Despite this, my mother and stepfather stayed together for the rest of their lives. I later found out that my mother was also hired out as a child, couldn’t learn a trade and had to remain a maid. She would have had the qualifications for a commercial apprenticeship.

Start with a handicap

I was born in Bern in 1930 as the illegitimate child of Fritz Pilcher. I developed pneumonia shortly after birth. When this had subsided, I was sent to the Elfenau infant home. A few months after the birth, the mother married the alleged father of the child. On February 13, 1931, they were formally deprived of their parental authority by the decision of the district governor’s office because they did not yet have a joint household and the authorities considered their care of the child to be inadequate. The guardianship placed me with foster parents in Lyssach for just under a year. In December 1931, my mother and stepfather took me back to Bern. However, I was immediately picked up again by the authorities and taken back to the foster family. Since this event, my mother and stepfather refrained from any contact. My foster parents had leased a small farm, which they ran with their four daughters. In the spring of 1935, they bought a larger farm in Aefligen themselves. I felt I was in good hands with this family. I still didn’t know what a Verdingkind was, nor that I was one myself.

Housed and marginalized

When I was about ten years old, there was an argument between me and my daughters while I was washing up. I threatened them that I would tell their mother, but the girls replied: “You don’t have a mother!” Now the farmer’s wife scolded the daughters for blabbing the secret.

Luck in misfortune

I screamed and cried and ran out into the courtyard and straight into a tree. I screamed even louder, couldn’t understand the world any more and wanted to disappear. Then I ran back to the house and took out the long gun I had left behind the front door. I wanted to end my life. Only the long rifle was bigger than me. I tried to put the barrel in my mouth and pull the trigger. The scene is still vivid in my mind today. Luckily I was too small and my arms were too short. I thought I could pull the trigger first and then reach the end of the barrel. The shot went off, the bullet grazed the ring finger of my right hand and landed in the ceiling. I was paralyzed by the bang. The foster mother rushed over, took the gun and put it back in its place. I never picked it up again. But I couldn’t come to terms with what had happened for a long time. From then on, I often hid in the farmhouse because I was looking for protection and the house gave me that. When I was called, I kept quiet as a mouse in the hiding place. The daughters would then search for me in vain. If they didn’t find me, they claimed that I was “roaming around” somewhere in the village. But I never intended to do this for fear of being beaten up in the village.

Past death

At Christmas I always received a pair of clogs, socks and an apple. To make the clogs last longer, my foster father had the village blacksmith make an iron ring around the shoes. This meant they could always hear where I was. And that saved my life. I was 8 years old. I was at school in the morning and we sat at the table in the parlor for lunch. After lunch, the two daughters cleared up. The foster father and foster mother stayed at the table. The foster parents were busy with the post and reading the newspaper. Then I said that I had to go to the toilet. The foster mother said: “So go, but I’ll open the back of your pants. And in the loo, take care of your pants”. I ran out of the living room, through the kitchen, through the hallway, over the “Bsetzistein” towards the outhouse. But I didn’t get that far. After the “Bsetzistein” would have been the wooden floor and then some cement floor. But after the “Bsetzisteinboden” it went quiet and Jean disappeared from the scene. Of course, the foster father heard this and realized that the cesspit was open. He had been spreading manure in the morning and had not covered the cesspit. The foster father ran to the open cesspit and looked down. He saw three small spikes sticking out of the slurry. Then he reached down, grabbed my hand and pulled me out. The foster mother and daughters were called and they had to fetch water from the well in front of the house. They took off my clothes and poured the water over me. When I was clean, they wrapped me in cloths and carried me into the living room and sat me on the stove. And the whole afternoon was spent in a depressed mood. They knew full well that the foster father had negligently left the cesspit open. There’s nothing in the files about this incident, even though Steffen’s neighbors had noticed everything.

Demanded early

I had to lend a hand with all the work in the fields and stables. Fortunately, I soon became familiar with the animals and I was particularly fond of the horse, which I was allowed to guide and lead. Yes, the horse was very kind to me. It was a magnificent gray. That’s why my foster family in the village called me Schümelipuur and I was called Schümeli-Verdingbub.

Mental distress

Like most of the Verdingkinder, I was a bedwetter. Because the bedding didn’t dry well in winter, I had to sleep on straw in the stable. But I had a faithful companion, the farm dog. At my new place of residence, in Aefligen, I was particularly harassed by the cheese maker and his two sons. These sons would lie in wait for me on my way home from school to beat me up. But there were a few families in the village who stood by me and welcomed me. Visits from the authorities were rare. Twice a year, the welfare officer, Miss Küry, who was well-disposed towards me, appeared. That’s why I have fond memories of her.

Consequences of vaccination

During my school years, the obligatory smallpox vaccination gave me a bad skin rash, which led to me being banished to the Jenner Children’s Hospital in Bern for a few weeks. After my recovery, I was not allowed to return to my former foster family. During my absence due to illness, my guardian had already placed another boy with a farmer. I was passed on to another foster home, but after a short time difficulties arose there. Even as a fourth-grader, I was abused as a worker, regularly beaten and punished.

Escape, punishment and harassment

I ran away, was picked up by the police the next day and sent by my guardian to a work institution for boys with serious educational problems. I stayed there until I left school in the spring of 1946. The director, called the father of the home, was a tyrant. He constantly gave me painful blows with a willow stick on my hands or the seat of my pants. However, because I was a mediocre pupil, I was rarely punished. But I was repeatedly bullied and embarrassed because of my bedwetting. The boys who wet the bed had to stand against the wall in the dining hall in the morning while their classmates ate breakfast in front of them. Afterwards, they only had dry oatmeal and nothing to drink all day. I made do by quenching my thirst with water from the toilet bowl. Late in the evening, the bedwetters were woken up again and sent to the toilet. The warden on duty discovered that I had had sexual contact with another boy because he found us both asleep in the same bed. The older, stronger boy had tempted me. And I had allowed the sexual assault to happen because this fellow pupil always protected and defended me in arguments.

How I found the “parents”

It wasn’t until I was eleven that I met my mother and stepfather one Sunday. I first walked past them twice around the house. The third time, my mother called out: “Gell, you’re Jean!” “No, I’m Hans!” I replied. Until then, I hadn’t been called by my baptismal name, even though it was correctly noted in my school records and school report. My mother had fathered three more boys with my stepfather. Two of them lived at home, the third was in out-of-home care like me. After this encounter, I continued to have contact with my relatives, but a real relationship never developed: “The half-brothers were privileged, but I was ridden around on.”

How I held my own in the work center

There was a strict order and we boys were given different tasks. In eighth grade, I was assigned to the mowing group. I was the smallest and weakest. But little by little I got stronger. And soon I was also asked to mow grain. “There was someone there, and I managed to find my place and get back on my feet.”

Apprenticeship in a roundabout way

After leaving school, I would have liked to start an apprenticeship as a mechanic. Despite passing the aptitude test, my wish was not granted for financial reasons. So I ended up working as a farmhand for a farming family. “I was advised to consider another profession. In 1947, I started an apprenticeship as a gardener in Seeland. I also had board and lodging at the training company. At that time, I also worked on Sundays. After two years, I was sexually assaulted by the master’s son. When I was 18 years old, I stole the second son’s motorcycle. However, the night-time joyride ended in a tree because of the bumpy road and my lack of riding experience. I was injured and the motorcycle was badly damaged. I was scolded and locked in my room on the first floor. I escaped from there and went to live with my “parents” in Emmental. I looked for work in the village myself and found it on a building site. When I had the money to repair the bike (250 francs), I went back to my former master and paid for the damage. The master wanted to keep me, but I no longer wanted to stay with him after the sexual assaults by his son. The guardian found me another apprenticeship in Villars-sur-Marly. I liked it and the master was also happy with me. The only thing that never happened was the promised salary. But I got enough tips from the customers. And I even passed my final apprenticeship exam with flying colors. After that, I worked in a seasonal job near my parents. In July 1950, I was supposed to start recruit school. I postponed it so that I could finally leave the guardianship.”

End of guardianship and escape to France

“When I applied to be released from guardianship, I also asked for my bank savings account. Both requests were granted, but the account was empty. I traveled to Paris by bike and tent. When I returned to Switzerland in 1952, there was unemployment and finding a job in a nursery was almost hopeless. That’s why I took on all sorts of jobs so that I could earn a living.”

Further training and independence

“Because I could work in garages, I also became a driving instructor. Due to a lack of money, I took a van in payment from a learner driver and started to gain a foothold in this

industry. The timing was right and I really got to grips with it. Quite quickly, I had a suitable fleet of vehicles so that I could also become active in the international transport business. Soon I was even getting orders to the Orient. However, it wasn’t just the trucks that suffered, but also the family. In 1983, I left the apartment and my wife. In 1987, we divorced. This is my life with its ups and downs. Since giving up the transport business, I have retired and hope for a few more good years.”

Text revision: Walter Zwahlen

Rita Soltermann

I was born in Burgdorf on December 31, 1938. My mother was a housewife, my father worked as a plasterer, he was employed in the town of Burgdorf. Unfortunately, this work, which was certainly very hard, was not conducive to his health, because he was very often ill in hospital, so that he died on February 28, 1943 at the age of 34 in the Inselspital in Bern. I was the second oldest of 4 children, my brother was born in 1937, I in 1938, my sisters Käthi in 1940 and Doris in 1941. We were all given a carer. According to the files, my father’s illness meant that we had already been supported by the welfare authorities for a long time.

Read more

Although not our fault, this was the first mark in our lives. Our mother remarried soon afterwards and our first half-sister was born in May 1944, followed by three more children.

Our stepfather didn’t get on with us children from his first marriage. He didn’t like us either, so he asked the guardianship authorities to place the four of us in a different home. This happened promptly that year. For me, it was October 12, 1944, and because the four of us children had been sent to different places, we only saw each other 2-3 times at most during our school years. I only saw my youngest sister for the first time when she was 68. She didn’t even know that she had three more siblings and that we were also deported just like her.

I was the youngest of a total of 14 Verdingkind over the years at this foster home. These small farmers in Emmental Gohl had no children of their own, and without the many Verdingkinder the work on the steep slopes would have been impossible to manage. We replaced the maids and farmhands they needed and had to work really hard. The farming family still received the cost allowances from the guardianship authorities. For me it was 360 francs a year. An important form of subsidy in those days. There was no running water in the kitchen and no electricity in the house. For the slightest offense, we got a slap in the face from the foster mother, or you had to drop your pants in the stable and then the carpet beater was used on your bare bottom. We also had to sleep two to a standard-width bed. I was a bedwetter until the 5th grade, like all my siblings. The room was unheated with ice flowers on the windows in winter. We had simple food, but at least enough. There was only time for schoolwork on Sundays.

From Monday to Saturday we had to work hard. Feeding and mucking out chickens and pigs before school. Then to school stinking and unwashed, tormented and teased by some of my classmates. Only one teacher was impartial. As we couldn’t bring any sausages or other delicacies, the farm children were preferred. We had to get our clothes from the older ones. We only had new ones for the exam. They were big enough to still fit for the next exam. I never saw the counselor who wrote the reports about me every two years. A Mr. Stucker always came by every few years. I had to show him my certificates and open my closet. There was a good snack for him. The two-year file note always contained the same wording; it said that she was a good child, was expected to work, the foster parents were doing their duty, her school report could be rated as good, could be better. As I was too small and slight and had a steep and long way to school, I was only able to go to school when I was nearly 8 years old and only finished compulsory schooling at sixteen and a half.

I wanted to be a hairdresser, but I would have had to go from Gohl to Waldstatt in Appenzell, where my mother and stepfather and family had lived for years, and from there I would have had to travel to St. Gallen every day to do my apprenticeship. We were sold off as small children. Now that I was half grown up, I was supposed to go back, who could understand that? Again, the main thing was that I was taken care of for the people in charge and their problem was solved! We all have a very good relationship with our step-siblings. The only alternative was to do a year of housework for 15 francs a month. That meant working for a priest from 6 in the morning until seven in the evening or even longer. His wife worked part-time and was stingy, but he was nice. They had small children and I enjoyed looking after them, I was used to working there and I liked it. After that I worked for a year in the household of a doctor in the same place. Later I worked in an office as an assistant. Apprenticeships were definitely off the table and I had to make my own way without any help.

I became pregnant at the age of 19. The guardianship authorities immediately got involved again. I was told to give the child away because it was just a burden for a 19-year-old girl. There were so many adoptive parents who wanted a child and the child would then have a secure future. Certainly better than with me, as I don’t earn enough anyway. But I fought tooth and nail against it. I now know women who didn’t have the same strength to fight back and had to suffer for the rest of their lives because they didn’t know where their child had gone. Blackmailing underage, unmarried girls was common practice and was much cheaper for the authorities. Back then, it was still a disgrace for an unmarried mother to have a child out of wedlock. During a visit to Langnau, I met my former boyfriend again and we fell in love. We got married and are still happy together today. Our four children are grown up and have given us eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. We have a beautiful and loving relationship and are often all together. We live in our own house which we have worked hard to build ourselves. But the stolen childhood will remain in my memory for the rest of my life.

Rudolf Züger

I was born on February 23, 1942 as the second youngest child. Four sisters, a half-sister and two brothers were born before me. The youngest sister followed later. My mother was an adopted child. My father remained an unskilled worker with various temporary odd jobs because he had no apprenticeship. At the time of my birth, he was working as a peat cutter in Oberägeri. I spent the first 16 months with the family. As there was nowhere for the family of many to live, my father tried to get rid of all the children and send them to a children’s home.

Read more

He was supposedly interested in a good Catholic education. He found a place for five of us in the now infamous home in Fischingen. I first ended up in the infant ward. It soon became apparent that the father was not paying the promised boarding money. And the home community refused to cover the costs.

Eventually we ended up in the poorhouse. As I was a bedwetter, I was repeatedly subjected to draconian punishments there. As a small child, I was forced to wash the soiled bed linen myself and as punishment I was always locked in the stable with the big black sow. I was in agony from fear. They often put me on a pot in the evening, threatened me, but forgot about me, so that I often never went to bed all night. I also suffered beatings. In winter, I was banished to the chicken coop, inadequately dressed. A passer-by discovered me there, got me out and took me to hospital in Lachen in a half-frozen state.

After that I went to St. Joseph’s Home in Bremgarten. The matron there was good to us children. But the nun in the ward had a bad attitude towards me and bullied me. She made me wear shoes that were too small and I ran around in them. Because a fellow pupil pushed me into her while we were showering together, she became furious, dragged me to the bathroom upstairs, threw me into the ice-cold water and practised waterboarding. I was shocked and wanted to throw myself off the roof of the home to put an end to my misery. Another sister, recognizing my plan, lured me back to safe ground with the help of a friendly fellow pupil and an apple. Under the false promise of an excursion, I was brought back to Fischingen the next day. I stayed there from the 4th grade until I left school.

In the guardian’s reports, I was categorized year after year as moronic, with bad dispositions, lazy and hot-tempered. Here, too, bedwetting was a shameful display in front of my peers. This was always followed by various cleaning and housework tasks as punishment. I actually wanted to become a priest or a nurse. My guardian objected on the grounds of lack of character and intelligence. I was therefore sent to a farmer in Ruswil

The drudgery started again with this farmer, who employed two more Verdingkinder in addition to his own two children. I had to be out grazing again at 4.00 am. The drudgery usually went on until 10 or 11 pm. I got the same food as the farm dog. The farmer’s wife also claimed that I had physically attacked her. In this renewed misery, where I was intimidated and didn’t know how to defend myself, I had the thought of suicide a second time. I was then placed with a foster family in Beromünster as a caregiver. In this one-man business for stove-making, oven and fireplace construction and tiling work, I continued to be exploited and was required to do a lot of extra work around the house, looking after chickens and rabbits, gardening and gravedigging. At least I was at the family table, got the same food and was somehow a member of the family.

After three years, the caretaker turned up one day and suggested that I could do an apprenticeship as a nurse. The ulterior motive was to find me a cheap servant for the assigned hospital. I was also sexually abused there by the office boy. One day, the third eldest sister called me and invited me to her wedding. However, I was forbidden to attend. After a possible apprenticeship as a chef didn’t work out either, I looked for my parents with the help of a coworker and went back to them. But then all hell broke loose again. My father worked against me, messed up various jobs and one day threw me out again. I applied for the advertised job as a predator keeper at the Knie Circus and was hired, even though I was wanted by the guardianship authorities. I was honest and testified that I wasn’t afraid of predators, but I was afraid of the authorities and bipeds. I was able to work there for two seasons.

Because my boss was moving to Italy with his animals for a new engagement, I couldn’t go with him because of the missing papers and the still ongoing manhunt. After that, I stayed with a farmer again for a short time. Despite the guardian’s initial resistance, I managed to free myself from this shackle for good. Later, on my own initiative, I trained as a nurse and did an apprenticeship as a printer. What I will never forgive my guardian for is that he repeatedly refused to provide me with emergency medical assistance in various emergency situations. I still suffer from the health and physical deficiencies today. He also wanted to commit me to the psychiatric clinic where he had already registered me shortly before releasing me from my guardianship.

Paul Schwarz

In 1972-76, Paul Schwarz was placed with horrible farmers in the municipality of Belp by the guardianship authorities because of his parents’ divorce. It’s almost unbelievable what he had to suffer and experience. Although highly intelligent, he was treated like the last servant and was barely allowed to do his homework, so that he finished secondary school with lower grades than he deserved. After completing an apprenticeship as a landscape gardener, Paul Schwarz emigrated to Canada, leaving his bad childhood and bitter memories of Switzerland behind him, set up his own business and also made up for missing out on his university degree.

Read more

I was born on May 30, 1960 in the Münsingen district hospital. My mother was married to my father in her second marriage. She already had three daughters from her first husband. These were placed in homes or foster families. So I grew up without any direct siblings. My father leased a medium-sized farm in the municipality of Bern. Bern was also my home town. I attended elementary school from 1967. My parents’ marriage had been on the rocks for some time and they divorced in 1971. From 1969 to 1980, an official guardian was responsible for me. As my mother was not considered capable of caring for me and my father, as a single farmer, was now also unable to do so, I was subsequently sent to the Brünnenheim on the Dentenberg, where I attended the internal school. My parents were able to visit me once a month for a few hours at the home. There, the middle school teacher made every effort to ensure that I was able to take the entrance exam for secondary school, which I passed. From spring to fall 1972, I attended secondary school in Worb. As I lived a considerable distance from the secondary school, I had to be driven by car, which didn’t always work out well. The head of the home then told the guardian that they could no longer do this and that they would have to find another place for me. But first they wanted to see if I would even stay in the secondary school, as the first six months were only temporary. I passed the probationary period and so the guardian placed me with a childless farming couple in the Gürbetal valley in the fall of 1972. From there I was able to cycle to secondary school in Belp. I had a good relationship with my classmates, and although I wasn’t there until the end of year nine, I still receive invitations to class reunions and have even managed to attend two of them.

The foster parents were very strict with me. I had to work like a farmhand. I woke up at 5.30 a.m., first to the stable, then to school. I also did my chores at lunchtime, then back to school, and the afternoons off were never without work. After school, to the stable, “Znachtessen” (dinner), then finishing up in the stable. It was always lights out at 8.30 pm, unless there was late work to be done, such as bringing in hay or straw in the summer. It was like that, summer and winter, Sundays and weekdays. Even if there wasn’t actually any work, they always made sure that I didn’t go without. For example, every free afternoon down in the cellar for a whole winter, I cut all the firewood for us and my grandmother, who lived upstairs, first with a handsaw and then split it with an axe. There was never any question that the same thing could have been done in a few hours with a table cutter. They couldn’t and wouldn’t give me the afternoon off!

Of course, there were also lots of beatings. A small example: while the foster parents were having a nap, my “lunchtime duties” were to feed the dog, water the three horses, as there was no self-watering trough in the stables, muck out the cows, cattle and calves and mop the lower stables. Once, shortly after I came back up to the house, my mother went to the lower stables. Unfortunately, the dog had left a little present in the meantime. She thought this was another example of me being too lazy to keep things clean. She immediately called for me. When I was downstairs, she took me by the hair, put my face in the dog’s dirt and beat me up with her free hand. Fortunately, a neighbor who was riding past on his bike and saw her abusing me shouted something at her and put a stop to it.

Of course, I was always to blame for everything and always did everything wrong. There were beatings when the rubber boots broke, beatings when the rice broom was too worn on one side, beatings when I put the lightning hoe into the wood stove from the front instead of removing the hotplate and inserting it from above, there were beatings when the horses didn’t shine enough after brushing, and so on and so forth.

The farmer’s wife’s favorite chastisement was to grab me by the hair and shake me back and forth. As a result, she would pull my hair out “bucket by bucket”. It also happened that my classmates teased me about it. “Am I already going bald?” they asked me. As there was so much hair missing from my head, you could sometimes see right down to my scalp. The hairdresser also looked at my head for quite a long time once, then asked a colleague because he thought I had mange. Because sometimes a bit of scalp came with the hair, blood crusts formed. The farmer’s wife also liked to use the riding crop on me. While she held me by the hair with her left hand so that I couldn’t escape, she would whip my back with her right hand. Of course, the skin on my back was always full of bloodshot welts afterwards, and sometimes the skin even tore open. It was always a problem to be able to hide these welts during gymnastics. Showering was therefore out of the question and only once did a classmate confront me about it.

The farmer’s favorite method of chastisement was to slap me. I always had to stand up straight in front of him so that he could hit me with full force. If I tried to fend him off or bent away, the procedure was repeated until he was satisfied and said that it had been a good “slap”.

Once a month over the weekend, I could alternate between my father and mother. But to my foster parents, my father was just a small-time dirt farmer, and my mother, who had had mental health problems all her life and therefore received an IV pension, was nothing more than a lazy dirty whore. As the product of such a marriage, I was worth nothing, and would probably get nowhere professionally except perhaps as a pimp. The farmer’s wife was a staunch Catholic and originally from central Switzerland; she only ever saw the sexual side of things. But she was probably very sexually repressed herself, which I later found out frustrated her husband a lot. She always accused me of being a sadist and only making her angry out of spite, because it gave me sexual satisfaction. She always tried to catch me masturbating, suddenly jumped into the bathroom, ripped the curtain off me in the shower or stormed into my room late at night and pulled the covers off me. As 12-year-old schoolboys, we naturally talked about one thing or another on the playground, but I still had to learn a few things from a school dictionary. I was threatened several times with preventive castration so that I wouldn’t be able to have children of my own. In hindsight, this threat was certainly not meant seriously, but as a 15-year-old who had already experienced a lot, I didn’t know that. However, their aim was to humiliate me as much as possible, increase my horror and reinforce my feeling of inferiority.

At school, it was the only way I could get by. Often it wasn’t enough to do my homework. My school reports were always good enough to keep me in secondary school, but never very good. After measuring my IQ, the careers advisor wondered why I had such poor grades, because children with my intelligence usually ended up in “Gymer” and later at university. Something that also appeared in the guardianship report two years later.

I was finally able to view these files in January 2011 with the help of the “netzwerk verdingt” association. According to interviews with the foster parents, quote from January 31, 1974: “…that he is a little comfortable and forgetful. They also often had trouble getting him to do chores.” And from March 5, 1976: “He is very withdrawn, often absent-minded, which the foster parents then interpreted as insincerity and lack of willpower.” I could also read in the files that in 1976 they received CHF 300 a month in care allowance plus health insurance premiums for me.

My fate was certainly discussed in the neighborhood, but there was no one who wanted to improve it. The farmer was a member of various associations and committees and generally enjoyed a good reputation, so people probably didn’t want to interfere and risk a dispute over a foster boy. But I can remember two incidents. Once I could still hear the farmer’s brother having a row with her during a visit to the farm and saying that the way they treated me wasn’t normal. Then he stormed out of the house, packed his family into the car and drove home. We didn’t hear from him for a long time after that. Another time, a pensioner, a neighbor who came to our house for coffee almost every day and saw and heard a lot of things, made a similar remark. He also didn’t show up at the house for many months.

One night in the summer of 1976, the calves escaped from the pasture. I was already in bed when the farmer came home from a meeting and noticed it. He stormed into my room in a rage and got me out of bed to help him catch them. Of course, he blamed me and I got a good beating. When I lay back in bed afterwards, I knew that things couldn’t go on like this. I decided to run away that very night, put on my clothes, got out of the window and rode my bike to my father’s house. But out of sheer fear, I didn’t show myself to my father until he got a phone at the “Zmorgen” in Belp. He then spoke to the official guardian and managed to have the out-of-home placement ended. I lived with my father on the farm until spring 1977 and from there I attended secondary school in Bümpliz. I took turns going to my father’s two sisters, who lived nearby, for meals. I started my apprenticeship as a landscape gardener in the spring of 1977. As several apprentices were doing their training at the same company, we were accommodated in the company’s own rooms. Room and board were charged and we received a small apprentice’s wage. I spent the weekends with my father. After my apprenticeship in 1980, I continued to work before and after recruit school to earn some money. In 1981, I flew to North America and visited a Swiss farmer in Manitoba, Canada, whose father I knew from my apprenticeship. I first helped him with sowing the grain and then in the fall with the harvest. In the summer and the following winter, I traveled through Canada and the USA. I really liked the country and the people. It was a more open society than in Switzerland, and I saw an opportunity to turn my back on my old life. When I returned to Switzerland in the late winter of 1982, I immediately applied for immigration at the Canadian embassy. In the summer of 1982, I emigrated to Canada for good. I founded my own horticultural business in Manitoba in 1985, which I still run today. I got married in 1992, we had a daughter in 1993 and a son in 1996. Because it is bitterly cold here in winter, which makes horticulture impossible, I work as a ski instructor in a small ski resort nearby.

The few people I have told about my life since then always ask a similar question: “Why didn’t you ever tell anyone?” A question I also ask myself today. If I can make a comparison, it is with an abused dog that has been on a chain all its life. Because he can’t jump away and his fighting spirit was beaten out of him as a puppy, he hides in a corner as best he can and endures the beatings, whimpering.

I always wanted to get away from the Gürbetal somehow, longingly calculating days, hours, even minutes and seconds in my head until school was over and I could go to an apprenticeship or somewhere else. But I also always tried to be good, to work hard so that I wouldn’t be such a disappointment to the foster parents. I was always angry with myself when I did something wrong. This anger gave rise to irascibility, which I have not completely overcome to this day. Deep down in my soul, I did love the foster parents and somehow desperately tried to be loved by them too, because they were the only ones I could love. The comparison to an abused dog, who is always loyal to his owner despite the abuse, is also appropriate here. That is probably also the reason why I put up with the farmer’s sexual abuse. A loving relationship with my real parents, like the one I had as a toddler and up to the age of eight, had long since disappeared and was almost impossible because of the limited opportunities for visits.

Although their childhood was different and they described it differently, I found similar feelings and experiences in the biographies of the other former Verdingkinder of netzwerk-verdingt. What a powerless feeling when you are only a “Bueb”, or “Meitschi”, as a Verdingkind, while the biological children get to feel “nest warmth” from their parents, and you yourself go away empty-handed.

The farmer died of a stroke in 1982 when he was not yet 50 years old. She died of leukemia in 1989. I stood at her grave and said the words: “I forgive you”, because they say that if you don’t forgive your tormentors, they will mistreat you emotionally for the rest of your life. But in the four years I spent there, what happened left too many scars on my soul. I may have spoken the words, but I know that deep down in my soul the damage done is too great, I will hardly ever be able to forgive them completely. In this sense, the abuse I suffered has not really stopped for me to this day.

Hugo Zingg

Hugo Zingg was born into a working-class family in the Matte district of Bern in 1936. His father was a mechanic. He spent his early childhood years in a children’s home in Kleindietwil in Oberaargau shortly before starting school. The owner, a hairdresser, looked after several other people’s children in return for a boarding fee. In the winter of 1942/43, he was hired out to a medium-sized farm in the Gürbetal valley. He was put to work in the fields, the household and the barn. He slept in the unheated, dark barn together with the young farmhand, who had also been a Verdingbub before him.

Read more

The mattress in the shared bed consisted of a straw filling in coarse jute fabric. The entire infrastructure of the farmhouse was old, but well maintained. In the living area there was a kitchen with a chimney, the farmers’ living room and bedroom, with two barns above. It was heated with wood. I had to drag the wood into the kitchen, light the fire, cook the pig’s trough, wash the dishes, clean the floors, beat out the carpets. I had to help graze in the fields, feed the horses, cows and pigs in the stable, muck out and take the milk to the dairy.

My way to school took ½ to ¾ hour in winter, depending on the amount of snow. In summer, I had to bring lunch to the people in the fields first. Because of the long walk and the short school lunch break, I often didn’t have time to eat. In winter, it was the same procedure when they were cutting wood in the forest. I never had new clothes or shoes until I was confirmed. I had to wear old ones that were usually too small. There was no underwear either, you just stuffed your shirt into your pants. I find it extremely worrying how a child could be constantly exploited through never-ending work. In my eyes, this is a crime. Development as a person was consistently stifled. I only had a good relationship with the animals. Instead of rights and development opportunities, there were beatings and scolding.

There were only moments on the way to school when I enjoyed a bit of freedom. I went to school because of the teachers and because I had to go to school, learning was secondary. The teacher gave me my own skis from Pro Juventute. For the farmers, this was a useless expense for a boy. At secondary school, we had a young teacher who did a lot of sport with us. But school trips by bike were taboo for me. I missed x school hours because of the work on the farm. None of these absences are noted on my report card. The teachers were always bribed with generous gifts in kind at Christmas. My whole childhood was a constant treadmill in an unreal, closed-off world with its own laws. For example, I was served the unloved sauerkraut at my confirmation dinner. The farmers themselves went out to eat.

The farmer’s wife liked to chastise me with a leather strap several times a week. I was also a bedwetter. Every unpleasant incident, every mishap was clearly my fault in her eyes and led to beatings. From the 8th grade onwards, the farmer’s wife delegated the punishments to the farmer. He simulated the procedure with me in the Tenn, he hit something and I screamed. The farmer’s wife never found out what was going on, but she enjoyed the reprimand. She was actually mentally ill. She also suffered from megalomania, terrorized her husband, son and servants, bribed the teachers and the policeman, gave orders in the village and flaunted the farm estates.

The suicide of the young farmhand, who, like me, had been shamelessly exploited and therefore took refuge in alcohol, made the authorities aware of the situation towards the end of my school days and they took me away from there. One day, I had to take the train alone to the careers advice center in Thun. Out of sheer fear, I failed the various tests because I was shaking. A day later, I was sent to a doctor who didn’t know my situation. He also didn’t realize that I was completely perplexed and unsuspecting when he tried to explain it to me. Then they decided over my head that I should learn plumbing. The farmer’s wife then went on to inflict psychological terror on me by painting my future in the darkest colors, reproaching me for my bedwetting and my previous behavior.

I was sent to a master in Seeland with board and lodging on the farm. There I was exploited again by not having any free time and having to go back to the farm during the vacations and Christmas, where I was welcome to do farm labor to redesign the cheese dairy. As I had no time to study for trade school, one day a man from the apprenticeship committee came to the master and ended the apprenticeship. I was then sent to the Bächtelenheim in Wabern for several months. There I worked in the carpenter’s workshop, the nursery and the farm. The director was a great-grandson of Albert Anker and was very decent to me, but realized that I was in the wrong place. The next stop was La Neuveville. I worked there for a year as an outworker for the milk trader and was again exploited. Instead of having afternoons off like my colleagues, I had to help out in my son’s vegetable business. But for the first time, I had the evening off.

At the age of 19, I was promised that I could start agricultural school in Courtemelon in April. But when winter school started, I was told that I would not be able to continue school because I had to go to recruit school in January and was offered responsibility for the pigsty for the remaining months. I had been screwed over again. But at least I learned the French language. In preparation for recruit school, I had secretly attended a Morse code course and received my identity card. When I was drafted, I was assigned as a radio operator in aeronautical radio transmission. After the RS, the school commander gave me the privileged position of personal assistant to the test pilot in Dübendorf. However, the entry about paternalism in my service record book cost me this position a short time later. And even later, the paternalism and the repression repeatedly cost me restrictions, suspicions and jobs. Until I realized it once and left out my burdened past history in my application letters and CVs. Before that, I was naive and inexperienced for a long time.

From 1970 onwards, however, things suddenly started to look up. It was only relatively late that I knew how to distinguish between reality and appearance. My past no longer played a role in my professional life. Thanks to my hobbies, I was now able to develop myself and get to know a different world. By working intensively with sound, film and video recordings, I found my own expression, got to know many new, sometimes prominent people and became competent through the numerous portraits.

Interview from 19.7.2011. recorded by Walter Zwahlen

“I experienced this horror myself”

The view, 12.10.2011

Armin Leuenberger

I was born on October 13, 1945 in Tiefenauspital in Bern. My biological parents were unmarried and did not live together. I was given my father’s name, Armin Bächli. My mother had a guardian. I was also assigned a guardian in 1947. In a curious procedure, the Zurzach district court denied paternity in 1946 at the instigation of my home community because my father was in prison at the time. I was now given my mother’s surname, Leuenberger.

Read more

Children’s home

I spent the first three years of my life until 1948 in the children’s home in Wohlen.

Hired out

At the age of 3, I was placed with a large farmer in the city of Fribourg, who had two children of his own, a boy and a girl, both a little older than me. My name was now Jakob Zbinden. In the 3rd primary class, however, my teacher intervened and suddenly I was called Armin Leuenberger again. There were two barrows and two milkers employed on the farm, as well as a maid. One milker was very violent and cruel towards me. All of us, including the farmer’s children, had to get up early and work very hard. I stayed on the farm until I was 16.

Terror on the way to school, school and church

As I was the youngest on the farm, I had to make the 5-kilometer walk to school alone. The teacher was stubborn and biased. Every December, he announced to the class that I had to pick up my shoes and clothes, which were paid for by the Canton of Bern’s welfare department. But I was on the farm of the richest farmer. The priest also made my status clear to me.

The mother is hiding

Shortly before my confirmation, the maid suddenly disappeared. When I wanted to know the reason, I was told that it was my biological mother.

What now?

At the end of compulsory schooling, the son of the farmer who now ran the farm told me to look for a job. At the age of 17, I became a contract thresher on a new machine and earned my own money.

Office apprenticeship, commercial school, salesman, marriage

I then started an office apprenticeship at the Fribourg company Michel for building materials and tools, which I dropped out of after two years. My next step was to get my license for cars and trucks. Then I completed commercial college. After recruit school, I started as a sales assistant at Coop in the Berne region, but was immediately sent for further training and soon became deputy store manager. My first love was a cheesemaker’s daughter. When we got married, we started our own dairy business, which was less profitable than we had been led to believe. We also had disputes with the trade association about opening hours. The divorce ended this attempt.

Truck driver and second marriage

Now I worked as a truck driver again for a while. Then I met my second wife. Our first daughter was born in 1970 and the second in 1973. Having a family was not compatible with the many absences in this job.

A detour to my own business

After a brief stint as a door frame fitter, I started out as a flooring salesman, attended courses and then obtained a diploma as a VSTF specialist consultant. In 1985, I set up my own business, which I ran successfully until a few years ago.

Kurt Gäggeler

Read more

Elisabeth Marti

Read more

After a while she returned, but had nothing else with her. Later, I realized that she wanted to delay saying goodbye, which she found difficult.

I came to live with the Röthlisberger farmers in Bomatt near Zollbrück (BE). The village was part of the large municipality of Lauperswil, where there were many small farms with lots of children who had been sent away. Röthlisberger’s son was already doing an apprenticeship as a butcher at the time, so I grew up there like an only child. I was always homesick for my mother and my three brothers and felt very lonely. Only our youngest brother was able to stay with his mother, who worked as a maid or housekeeper for various farmers. I myself had to work very hard as a child. Because I was still so young, starting any new job proved to be difficult or even difficult. Nobody guided me, helped me or considered that I was being asked to do too much.

I remember the farmer’s wife as a very nasty woman. She often beat me with a carpet beater. Sometimes such a punishment was so brutal that I couldn’t sit or go to school for two days. During this time, I could only eat standing up. Nobody monitored the conditions of my placement. There were 14 children in my class of around 30 pupils. One brother was placed with another farmer not far from me and had it far worse than me. His teacher was very biased, which is why the socially weakest had to suffer the most under his regime. I loved my time at school and, looking back, I don’t see it as a disadvantage. I had trouble with mental arithmetic. If I couldn’t see the numbers in front of me, I was lost – unfortunately the teacher never understood that.

My mother was only able to visit me briefly 1-2 times a year at most, as she changed jobs and had little free time. She usually came by bike, sometimes from far away. She thought I had it right there and only found out much later about all the torment I had to endure. My foster father was kind to me and never hit me. However, he worked in a factory during the day, so I was at the mercy of the farmer’s wife most of the time. However, when he was at home, I sought his company by helping him with his work. He also had to suffer from his wife’s viciousness. Even his son was not safe from her wickedness. He later took his own life. At the time, I tried to console myself by telling myself that the farmer’s wife couldn’t love me because I wasn’t her biological child. The certainty that I would be able to leave this place again after school was a source of support in times of need. But the isolation, loneliness and the misery that came with it always caught up with me. I was always homesick for my mother and my brothers. Once I even thought about suicide. During the years of the Second World War, the farmer’s wife always sent me to the neighbors to exchange the food stamps I didn’t need. I was very fond of this haggling and bartering.

I actually wanted to become a pediatric nurse. But after school I went to work as a nanny for farmers above Morges (VD) for a year in French-speaking Switzerland. I didn’t learn French there, however, as they were Swiss-German. From there, they sent me to live with relatives above Montreux for six months. I then found a job in a crèche and later in the kitchen and as a nursing assistant at the hospital in Langnau (BE). The chef was from Glarus and intended to return to Glarus to take over his own restaurant. Because his wife was expecting their second child, he asked me if I would like to come with them to help his wife with the housework and look after the children. That’s how I ended up here. I didn’t really like working in the restaurant and wasn’t often asked to do so.

It was in Glarus that I met my future husband. We married in 1955 and our first son Ernst was born in the same year. Two years later, the second, Werner. With the money from the compulsory portion of my grandfather’s inheritance, my biological father’s father, we were able to take over an electrical store on August 1, 1959. Unfortunately, my husband contracted polio with meningitis in 1960. This left him with frequent headaches and muscle weakness. So I ran the store, including the office and bookkeeping, mostly on my own. We were eventually forced to give up the electrical store. Together with the mountain guide Frigg Hauser, I founded a mountaineering school, which we later turned into a mountain sports business. I still run it together with my daughter Anna-Elisabeth. On my trips to Bhutan and Nepal, I learned about the poverty in these countries. I committed myself to making things better for these people.

Uschi Waser

Read more

Veronika Ursula Ammann-Lehmann

Read more

Herbert Keller

Read more

The Schönebergers were actually planning to adopt me. However, after a few years they had a child of their own. I didn’t cope well with that.

I then went to other foster homes in the canton of Glarus. When I was 6 years old, I was taken to the children’s observation center in Brugg in the canton of Aargau for a year. At the age of 7, I was transferred to the children’s home in Effingen AG, where I stayed for nine years. I completed 5 years of elementary school at the home itself. From there I went to secondary school in Bözen. After school, I went to an external vocational school for a year, but still had a separate room in another building of the home.

During my time at the home, I was sexually assaulted several times by a teacher. However, this was never investigated. When I visited the current home in Effingen in 2020, I was hardly able to find out anything. They continued to keep things quiet there. I only found out later from the files that I had another half-brother who was also in Effingen with me for 7 years, without us knowing about each other.

In 1962, I started a 4-year apprenticeship as a book printer in Wallisellen. During this time I stayed at the Brüttisellen apprentices’ home in Baltenswil in the canton of Zurich. I completed my apprenticeship in 1966 with a diploma. My home files are very extensive. Those of the guardian and the authorities in Effingen are 100 pages long, full of all the smallest misdemeanors. In 1946, a doctor in Tägerig AG examined me. He mentioned in his diagnosis that I couldn’t really put down roots anywhere. In 1951/52 I had several asthma attacks. In 1953, I was sent to a home in Feldis in Graubünden for a year. After that, I was taken to the children’s ward in Rüfenach in the canton of Aargau.

The files from this time are very different, but not very professional. At least it was noted that Herbert suffered from not receiving any mail or visits. The various assessments or even age tests when I was between 6 and 8 years old are largely amateurish from today’s perspective. Insignificant things that a normal person would know how to classify are overrated. Or the findings of the doctor at the cantonal sanatorium and nursing home Königsfelden AG of February 5, 1953 to the official guardianship of Lenzburg about me tend to be based on false assumptions, today I would have the right to demand correction of the files. After my apprenticeship, I worked for two years as a printer at Conzett und Huber.

Addendum to my commitment in the Foreign Legion

In December 1968, I crossed the border from Geneva to Annemasse on foot with a small suitcase and a few clothes. Over the next few months, I traveled around the south of France, then lived in Marseille again and had various temporary jobs there. I also got to know former Foreign Legionnaires there. On April 25, 1969, I signed the legion contract myself in Strasbourg for 5 years. In May of the same year, I arrived at the barracks in Marseille and on June 1, I went by ship to Bastia in Corsica for training. From there I went south by truck to Bonifacio, where I got my driver’s license and then trained in various stages and other places. I became a corporal there at the beginning of February 1972. In June 1973, I went to Djibouti in East Africa via Paris. At the end of September 1975, I returned to the south of France and worked there for some time in the print shop of the Legion Center in Aubagne. In February 1975, after 7 years of service, I took my leave. The reason for my commitment to the Foreign Legion was the long years in the children’s home and the feeling that I had no home and nowhere to settle down. Fortunately, I was never injured during the 7 years.

Boris Scavezzon

Read more

I sensed their fears, but didn’t understand why. The expression Tsching accompanied me every day in those years, including the additional remark that my parents were stupid because they didn’t speak German properly. As time went on, I began to tell off the children who insulted my family.

I went to a special school and should have stayed there after the second grade. My limited Swiss teacher at the time was of the opinion that I wasn’t capable of transferring to a normal class. In fact, my special school report was just satisfactory in arithmetic and writing, and there were no other grades. A school psychiatrist, who I can still remember today, was of the opinion that I could go to a normal class, but his assessment was obviously ignored.

By chance, my father met a work colleague who sent his children to a children’s home in Näfels, which was run by Swiss nuns. I was actually allowed to attend the normal class in the canton of Glarus and was “suddenly” a good pupil. However, I had to work hard for the first time in my school life and realized that you could actually learn something at school if it wasn’t a special school! Decades later, my mother told me that one day she had received a call from the special school teacher suggesting that I should come back to Zurich. However, I would then have to attend the special school again, but they would look after me “well”. My parents refused and my mother burned my school report out of anger and I had it printed out again decades later. It should be mentioned at this point that the children’s home was not free and my parents had to pay for me. As a painter and seamstress, they didn’t earn that much, but they managed. They beamed every time they saw my report card, because I had an average of between a 4.5 and 5. On the other hand, they regularly argued about money.

I even learned something new in Näfels. We children from the home were regarded as “home children”. Not quite full-fledged, to put it nicely. There was no difference whether a home child came from Italy or Switzerland. That surprised me, because until I moved to Näfels I always thought that the Swiss only had something against Italians. The Swiss also seemed to have something against certain Swiss people? Many of these Swiss children became my friends and often supported me, as I did them.

In sixth grade, we had a teacher called Müller. In his opinion, the most intelligent pupils sat in the back row (I sat there) and the ones he didn’t like sat alone in the front rows. He always referred to a slightly chubbier boy as Kartoffelsack (potato sack); this boy became my friend and I noticed that he suffered greatly as a result. At the end of year 6, everyone had to take a cantonal exam. Anyone who achieved a grade between 4.5 and 5 and also had this average grade on their report card was allowed to go to secondary school and I made it. However, there was also a monastery school for boys in Näfels at the time and you had to take another entrance exam there. Some of my home mates advised me not to go to the monastery school they attended. Their reasoning: If you have to live with nuns, you don’t have to go to school with monks! It was enough that I went to the exam with this conviction to be the only one from Näfels to clearly fail the convent school exam. What a shame from the nuns’ point of view and what a joy from mine. We boys were also given a new nun who didn’t suit me (and I her) at all. As a result, I was kicked out of both the secondary school and the children’s home. It was either she (the nun) or I had to leave, and it was no coincidence that I was chosen.

After five years in a children’s home, I therefore spent almost three years at a so-called Catholic boys’ institute called Alpine Schule Vättis. The school was next to the residential home and, from today’s perspective, we would call it a (three-year) lockdown, which was much stricter than the one that prevailed in Switzerland during the coronavirus era. Nobody noticed this little detail except the inmates! In secondary school, I did well again and my French assignments were copied by at least half the class. My class went down in history as the worst class. In fact, we once booed a teacher and sang “Grappa a la mela” (original song known as “Guantanamera”) to musically underline his alcohol consumption or flag. A supervisor once slapped me in front of the class because when he said that I wouldn’t even see him standing in front of the blackboard with my long hair, I replied that it didn’t matter because I would see one less idiot. There was also a math teacher who we called “Knacki”. He suffered from muscle atrophy, if I’m not mistaken, and liked to hit me frequently – he only hit me once, by the way. Apart from that, he insulted what he thought were stupid pupils by saying that their brains were only good as hair tonic. The history teacher, who suffered from bone loss and was proud of the fact that he was one or two centimetres taller than Napoleon, was a contrast to this. He behaved fairly despite his illness and as I had always liked history, I enjoyed learning and in time almost the entire naughty class 2b learned with me. In this subject, we were even better than the parallel class for once. Once again, nobody noticed what certain teachers were doing and the head teacher liked to think of himself as an uncle, which is how he wanted to be addressed – just like a certain Mr. Mengele decades earlier.

I had an average grade of 5 in my third year of secondary school and wanted to start a commercial apprenticeship in Zurich. I returned to this city in 1981, but nobody wanted to employ a former orphanage child, even though someone told me so directly. I felt that this supposedly free world was unfree because, in my opinion, almost everyone hid their feelings behind a façade. In my opinion, a free world should have been made up of people who walk through the world openly and that was obviously not the case. By chance and thanks to a personnel manager who was just waiting for his pension and reacted very late, I did find a job as a commercial apprentice after a delay.

There was still a youth movement in Zurich at that time and at some point I let my hair grow longer. One day, when I was late for school again, a teacher asked if I had spent the night at the AJZ? A school friend replied that I hadn’t, because he hadn’t seen me there last night. I reluctantly finished this training and over the next few years I mostly worked temporarily in the accounts departments of various companies. Adapting again and again helped me personally and made me better.

One day I was working with a student at the University of Zurich and told him that I would also like to study. He gave me the tip that I should attend the KME (Kantonale Maturitätsschule für Erwachsene) in Zurich. I didn’t know the school, but I applied. You have to pass two subjects in the entrance exam in a maximum of two attempts, namely mathematics and French. I passed math at the first attempt and French at the second attempt, as it had been more than ten years since I had taken it at school.

I didn’t really trust myself to go to grammar school, but I was proven wrong. This made me angry at the Swiss school system (which had forced me on a school odyssey that I would have very, very gladly done without and had given me the worst years of my life) and at myself, who had not realized for too long that I was capable of it. I decided to finish this school with the absolute minimum average of 60 points. I didn’t quite manage that with 61 points. I would like to add that even with the right attitude, I would have achieved at most around 70 points.

My career choices included special education teacher, history or an oenology degree. I opted for the third and it turned out to be a bad choice. Maybe you shouldn’t always make your passion your career choice. In the end, I didn’t complete this degree. Later, my mother became seriously ill and I wanted to help her. We will all die one day, but the question is how and this can make a difference. Unfortunately, no team came together to help my mother, who had breast cancer and dementia. She was placed in a closed nursing home on “Paradiesstrasse” (Vorhöllenstrasse would be a more accurate description) in Zurich. During my visits, she often asked me what she had done to be thrown into a prison. So shortly before she died, she experienced what I had experienced as a child without realizing it. Children and sick elderly people are the most vulnerable people, not only in Switzerland!

Later, a colleague suggested that I start studying history at the University of Zurich. As of 2023, I still have a seminar paper to write before I can start my Bachelor’s thesis. It should be clear to everyone what I want to specialize in…